If you’ve ever had the pleasure of training a brand-new employee, you’ll be well aware of the following fact:

They’re usually incompetent.

Of course, if they’re hired in from another organization, or have some relevant prior experience, it might be okay. Maybe they’re a quick learner. Maybe you’re extra patient. Maybe they even manage to avoid making you question your career choices.

Regardless, new employees are always going to face a period of adjustment, a period in which they struggle to perform as well as you’d like them to. There can be issues with adapting to an organization’s particular processes, learning to use new tools, or truly understanding the reasons why you do the things you do.

It can be difficult for you (or your managers) to know what guidance to give these newcomers. Some people will take a very hands-on approach, strictly guiding the employees over the first few weeks or months. Others will prefer to let employees “sink or swim” – after a brief initiation, they’re thrown headfirst into their role, learning as they go.

We can’t say that one approach is better than the other in all cases. It’s highly dependent on your own situation – what works in one sector could be an embarrassing failure in another.

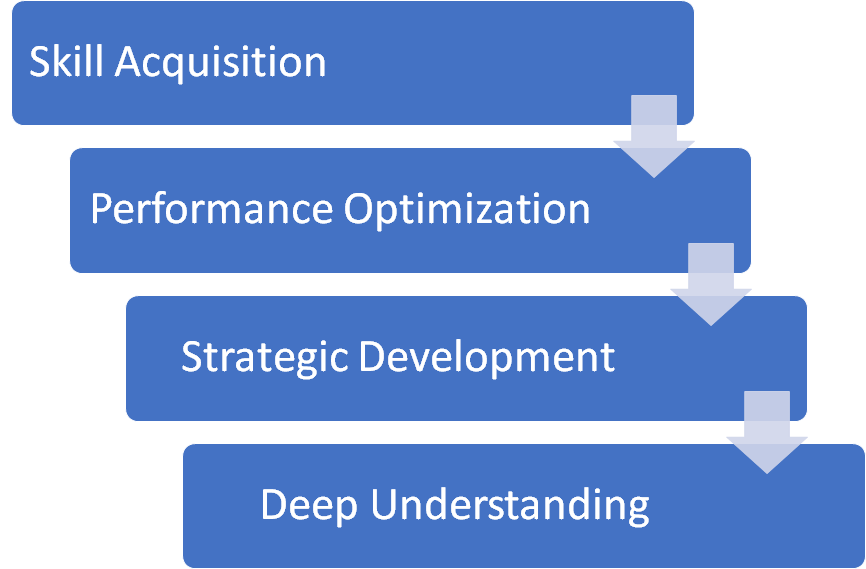

However, most employees (regardless of the role in question) tend to follow the same learning cycle. Depending on the business itself (and the person in question), the length of this process will vary, but the individual steps are almost always present.

Employees need their hands held throughout the initial stages. Obviously, this requires a lot of time from you, their supervisors, or whoever you’ve managed to trick into taking those employees on. After these early days, the employee gradually becomes more and more self-sufficient, eventually reaching a point of self-directed professional development.

As with everything else in life, the devil is in the details. In this article, we’re going to take an in-depth look at how the needs of your trainee change as they gain experience. To better understand this topic, we’re going to refer back to a useful model we’ve encountered in the past.

Pyramid Training Definition

Based on the title of this piece, you might have initially thought that this article would be about managers learning from their subordinates – higher-ups receiving some sort of training or guidance from those down below.

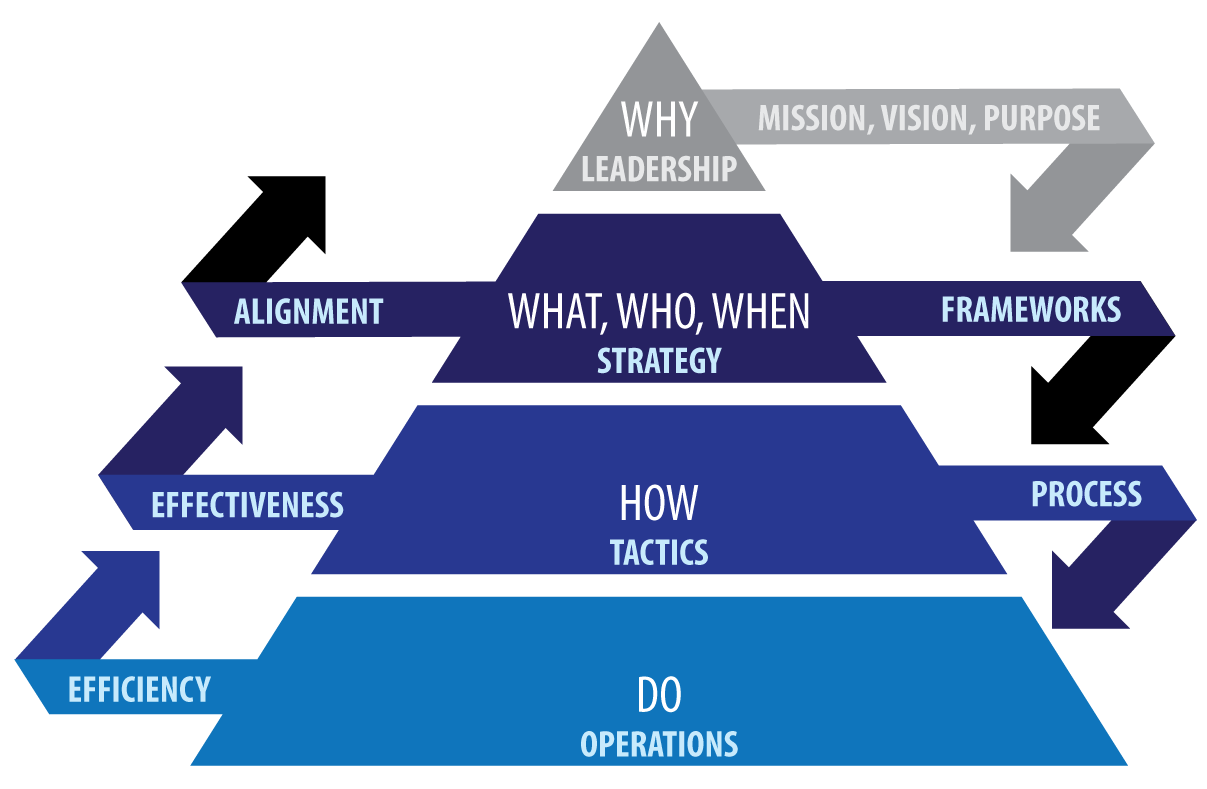

While that’s certainly a worthwhile topic of discussion, that’s not what we’re talking about here today. Instead, what we’re focusing on is how we can better understand training and development (particularly when it comes to new employees) when we consider our organizational pyramid.

Now, if you’ve read some of our previous articles, then you know we’ve used this image in the past. That’s because it’s extremely valuable, serving a number of different purposes. It helps us to understand how vision/mission feed downwards to the strategic, tactical and operational levels of the business, everything in perfect alignment.

Leaving that function aside, it also helps us to understand the training process.

Organizational pyramid maps

The organizational pyramid maps perfectly onto our learning model mentioned above. Employees move up the pyramid as they gain experience in the organization. When they first start out, their knowledge of what the organization aims to achieve is limited. By the time they’re done, they’ve gained a deeper understanding of why things happen the way they do and know how to move the business towards the achievement of its vision.

When you know how good the eventual payoffs are, it’s tempting to want to rush the process. Why would you want to spend any time on lower forms of training when it doesn’t help your ultimate outcomes?

And sure, you can speed things up with a rigorous onboarding program and lots of focus on buy-in… but no matter what you do, this process is going to take some time.

We’re well aware of this. Someone who has been at the company for 6 months will almost certainly understand more about the company culture than someone who’s been there for a week. Leaving aside their length of service, it’s clear that there are also other factors separating the two. The primary one is the quality of training they receive. By giving the employee the right kind of consideration at all stages of the journey, you can ensure that they end up just as you’d like them to – skilled, reliable and efficient.

Now that we’ve established the need to give attention to the employee at all points in the process, it’s time to move on. Next, we’re going to look at each level of the pyramid, in turn, explaining how the employee gets there, what it means to them, and how they best learn at this stage.

To relate this model in practical terms, we’ve referred to two examples throughout – training a salesperson, and training a new construction worker. By examining these two differing professions, you’ll be able to fully understand the lessons presented here.

What are the 4 Employee Pyramid Training levels?

Level 1. Operational (Skill Acquisition)

At its core, learning requires repetition and focus. The first few times you do something, it’s strange. You’ve never done anything quite like it before. The neural pathways/muscle memory demanded by the task are more like dirt tracks than the highways required to do it right.

Over time, this will change – but that’s the critical point here: it takes time. The process can be sped up by having effective procedures in place, giving adequate attention to the needs of the trainee and ensuring that they’re getting the best instruction possible…

But no matter how many of these shortcuts you take, the process is still a process.

Think back to a time when you started a new job. I’m sure that, at first, there was a lot of different things required that you didn’t know how to do. Being shown how to do it once wasn’t enough – you made plenty of mistakes which needed correction from the people training you.

Fix your mistakes yourself

However, after a certain period of time, you noticed that things were just starting to “click” for you: what was once impossible to do correctly started to become easier and easier. Even if you weren’t doing it right every time, you pretty much knew enough to fix your mistakes yourself.

You may be faced with training employees who have “prior experience”. While this seems good on the surface, it’s often more trouble than it’s worth. It’s all well and good to know how to do something, but if they’ve learned incorrectly in the past, it’s a lot harder to ingrain proper habits now. The self-correction mechanisms that we discussed above may not be present in this employee – you don’t know how good the training they received was.

The best approach to take in this situation is to train them from scratch anyway as if they’re brand-new. If they already know how to do something, then they’ll have no problem demonstrating their skill. If there is any issues, you’ll catch them early on, fixing them before they become a real headache.

You have to be somewhat tolerant of an employee’s mistakes in the beginning. That’s the reality of bringing someone new into an organization – there’s a bedding-in process. As they get more familiar with the tools, processes, and tasks in question, these mistakes should dramatically reduce in number. If they don’t, you may have to evaluate whether they’re worth keeping on, or if it would be best for all involved to part ways. The length of time this process takes is going to depend on the industry you’re in, the role the employee is performing, their pre-existing ability, and similar factors. You’re the only one who can determine if things are taking too long, or if you’re just being impatient.

Achieve Particular Outcomes

In the initial stages of employee development, you can’t be too focused on achieving particular outcomes. Focus on learning the skill first, worry about refining the results later.

To illustrate this, think about an employee joining your sales force. If you’re training them from scratch, you have to make allowances for this inexperience. The number one issue which prevents most beginner salespeople from progressing is a fear of rejection. Depending on how your organization does business, this will manifest in different ways: not making cold calls, not meeting clients in the field, not following up on warm leads, etc.

To help this salesperson get over their fears, they need to commit themselves to the process of learning to sell. One of the easiest ways to do this is for them to commit to making a certain number of cold calls every day. With this provision in place, all they have to focus on is making the calls – the result of these calls is, at this point, irrelevant.

Take the salesperson aside, teach them your cold-calling process, give them useful advice… then step aside and let them start working. Tell them what their target number of calls is – depending on the size of your organization, this could be 10, 20, 50, 100, whatever. Their goal is to make this many calls per day, no exceptions.

This doesn’t mean that they pick up the phone, mumble quietly, and then hang up before giving the prospect a chance to respond – that doesn’t count as a call. To ensure that this activity has the intended effect, you’ll have certain rules in place. Speak directly to a decision maker, read from x script… whatever rules you select, make sure that they’re to help the prospect do the task correctly.

Build resilience

Once again, we’re not focusing on the outcome of the call – for our purposes, we only care about whether or not they actually make the call (as per our parameters). Build the habit of calling, of overcoming their fear of rejection, and of following the process now. This builds resilience and confidence in the employee, which they’ll certainly need if they hope to succeed in sales.

And this is not to say that we’re exclusively focused on one particular process (in this case, cold calling). You can work on multiple things at once with this approach, building the employee’s competence in several domains. They can cold call, tag along to meetings in the field, attend trade conferences, etc. Remember, the focus is on developing the ability to do particular tasks. Piling on too much new information will slow down progress in all areas, so be careful.

The learning process

The example of a new construction worker is a simpler one. Depending on their background, they may possess some of the skills required, or they may know very little. The learning process, although rarely articulated as such, is quite refined in these professions: the more experienced people will give the trainee little tasks to do, show them how to perform basic actions, demonstrate tool use, etc. Over time, the apprentice gains more and more experience, gradually being trusted with increasingly important work.

Teaching them to perform basic skills (e.g. driving nails, hanging drywall) under supervision is the first step in the process. They merely need to learn to focus on developing competency and doing as they’re told at first. Much like the beginner salesperson, they need to get over any issues they have (no coordination, lack of physical endurance, etc.) before everything else.

Determining whether or not a trainee has successfully executed on a particular task is a lot simpler when it comes to tangible trades like construction, plumbing, and painting. A more experienced professional will be able to examine both the work in progress and the end result, making a judgment as to how well they’re doing.

After the employee has developed the basic competency required to perform, it’s time to focus on getting better outcomes from the tasks. To do this, we’re going to look at how we optimize things at the tactical level.

Level 2. Tactical (Performance Optimization)

Now that we’ve managed to get our new salesperson comfortable with making cold calls, it’s time to start focusing on the outcomes they’re generating. It’s all well and good that they’re able to push themselves to hit the minimum number of calls for the day… but if they’re failing to convert any of them, their tenacity is worthless.

Similarly, our construction worker has now developed the skills required to contribute to a project. However, if they’re only able to help when they’re being closely supervised, they’re not a massive asset to the business.

Here on the tactical level, we’re concerned with optimizing their performance of a particular task. Paying close attention to our employee, we take a really deep look at how they’re going about things and figure out where improvements can be made.

Maybe our salesperson is panicking mid-way through the call – a squeaky-voiced, hyperventilating pitch is rarely an effective one.

Maybe they’re reading directly off a script with no enthusiasm, making the prospect feel as if they’re dealing with yet another uncaring corporation that’s only out for their money.

Whatever the case may be, there’s room for improvement.

This stage is the time for experimentation. There are many ways to achieve success in all areas of life, and selling is no different. Part of being a highly competent salesperson is developing the ability to know what kind of approach to take with a particular client – some will want you to empathize, some want to be sold on the benefits, some want you to fix a burning problem they have, etc. If your trainee hopes to make a career out of selling, then they need to learn how to actually sell, not just how to make a generic cold call.

In the case of our construction worker, they start to gain a little more autonomy in this level. In Level 1, the focus was on how to hang a sheet of drywall, and how to tape corners. Here in Level 2, the task is now to “finish the room”. Whether they do the ceiling first, or start with the walls, or hang all the drywall first, or do one section at a time is up to them. Mistakes may occur, but they will be learning experiences for the trainee. They should be encouraged to try out a few different ways of approaching the task until they find what is most effective for them. The processes drilled into them by their trainers will serve as invaluable guidance through this stage, but it’s only by taking on more responsibility that they will learn to coordinate the various skills and tools required for the job.

In a more general sense, this level is all about learning to apply the tools as well as possible for their intended purposes. A hammer in the hands of a careless amateur is as likely to break his own finger as it is to drive a nail. In the hands of a master carpenter, it’s a tool that contributes to the construction of something beautiful.

Credit: Pixabay

Your salesperson needs to learn to wield their metaphorical hammer more effectively… and your construction worker needs to master his literal one. Once they’re able to swing it properly, you then focus on getting them to do it as well as they possibly can.

However, as the old saying goes…

To the person with a hammer, everything looks like a nail

Level 1 and Level 2 are all about learning how to use the tools in question. No matter what skill we’re talking about (be it cold-calling, hanging drywall, or even something like data entry), you should follow the same process:

- Level 1 (Skill Acquisition): Learn how to do the task correctly. Our focus is on the consistently correct application, not on the results.

- Level 2 (Performance Optimization): Learn how to do the task effectively. This entails optimizing performance, as well as learning more complex uses for the tool (e.g. if Level 1 is basic data entry, then Level 2 is advanced spreadsheet production).

Progression to Level 3 requires that your employees fully understand the tools and skills in question. If they are still struggling with some aspect of their task, it’s important that they rectify this before moving on.

Failing to ensure that your employees are ready to progress to Level 3 can lead to an overreliance on one particular tool over everything else.

To illustrate this point, imagine a carpenter who can’t use a hammer.

Sure, not very realistic, but just play along for a second…

When he first started training, he was put in a separate area to everyone else, a saw was put in his hand, and he was instructed to cut planks to size. Hour after hour, day after day, he sawed and sawed and sawed. By the time he was done, he was a master of the tool – there was no one that could cut a board as well as he could.

Life is good for our carpenter. He’s really good at using a saw, and it’s the only tool he’s ever been exposed to – as far as he’s concerned, it’s the only thing he has to be able to use.

But then one day, he’s asked to drive some nails. Maybe he’s helping out a coworker, maybe someone’s taken the day off… whatever the case, he has a new task to attend to.

This man has never seen a hammer: all he’s ever known is the saw. So what is he likely to do when faced with the task of driving some nails?

In this situation, he’ll probably end up beating at the nails with the end of his saw, getting more and more frustrated as the tool he has mastered fails to deliver results on this new task.

A farcical example, sure… but you understand the broader lesson: blind focus on one approach above all else is not useful. Once we’re confident that our employees are using the tool as effectively as they can, it’s time to push upwards to the next level. Fail to do this, and you’ll be like the carpenter beating at nails with his saw – out of your depth and performing poorly.

At this stage, tracking work output over time is critical. You want employees to apply the skills they’ve learned in a variety of ways, always striving to find the most efficient arrangement. However, you don’t want to simply rely on what they feel works best – use real objective data to determine the best options to take.

You may find that your salesperson gets more conversions during certain time frames, or that your construction crew completes rooms faster if all the drywall is hung first and taped later. With this information, you can then set up work schedules to accommodate these optimal processes. The salesperson is instructed to complete all of their administrative work outside of peak conversion periods, and your drywall crews batch their work by a task to finish the job more quickly.

Of course, things change over time. You should encourage ongoing experimentation. As new tools, skills or technologies come to light, revisit your workflows to make sure that the way you do things is still the best way. If it’s not, then something needs to change. Regardless of the outcome, referring back to the objective data will provide the answer you need. Relying on this, instead of placing too much emphasis on your feelings, will ensure that you’re doing things right, not just doing things as you like.

Level 3. Strategic (Strategic Development)

Having pushed past their initial fear of cold-calling, and subsequently learning how to effectively cold-call their prospects, it’s now time to give our salesperson some more tools to use.

Back on Level 1, we focused purely on getting the employee to understand how to do a particular task. We didn’t worry about the outcome – within certain constraints, all we cared about was getting them to do the thing.

On Level 2, we turned our attention to optimizing their performance. Taking the tool they were using and refining their use of it, our efforts were dedicated to improving outcomes in this one narrow domain.

Now, as we ascend to Level 3, our focus on specific tools and rigid processes takes a backseat. Instead, we now chase the outcome we desire, using everything we have at our disposal to attain it.

In the case of our salesperson, they’ve received a good deal of training by now. They know how to cold call, they’ve met prospects face-to-face, and they’ve even managed to land a few clients.

At this stage, they can no longer cling to the familiar procedures that have guided them to this point. They now have to realize that the outcome they’re chasing (successful conversions) is more important than any particular tool at their disposal (e.g. cold calling).

We first discussed this back in Level 2, when our salesperson was learning how to optimize their cold calling. They found that different clients required a different approach – some wanted a friend, some wanted to be sold on the benefits, and some people were just desperate for their problems to be solved, no matter the cost.

Principles

The same principles apply on this level, but instead of concerning themselves with all the different ways to use a hammer, the employee must instead expand their awareness, determining the best tool for the job. Rather than blindly categorizing everything as a nail, they take stock of the situation, using their accumulated experience to make as good a judgment as they can.

When faced with the task of converting a particular client, our skilled salesperson has a number of approaches they can take to landing them as a customer. They can cold call, form a relationship over a longer period of time, seek a referral from existing clients… whatever path they take, they remain focused on the goal of conversion. The outcome matters far more than which tool is used.

In the case of our construction worker, this is the level where they start to gain the practical, real-world experience that sets them apart from novices of the trade. Practically anyone can learn to drive a nail, cut a plank, or hang drywall with enough practice. However, there’s a big difference between knowing how to use these tools, and knowing which ones you should use. Novel, non-routine situations are an everyday reality in the trades. The uninitiated might think that most houses are laid out the same… but the reality is quite different.

Electricians uncover wiring without any logical structure, plumbers attempt to understand the thought processes of the people who went before them, and construction workers, supplied with sub-optimal materials, do the best they can with whatever they have.

In all of these situations, the employee’s adaptability is being tested. They need to take the standard procedures they’ve learned and modified them to fit a new situation. They need to understand what tools (e.g. hammer drill or impact drill, cordless or corded, Phillips or flathead…) will be most effective for the job at hand. Doing things “by the book” is preferred, but not often realistic. In the words of Theodore Roosevelt, their motto is:

Credit: Quotesville

Your employee’s ability to take a strategic approach to the situations they face is a huge asset. By continuing to develop their skills, they will soon progress to the next level of the pyramid – not a new level, exactly, but a more advanced version of this one.

Level 3.5. Even More Strategic (Deep Understanding)

At this point, the employee has transitioned from a fresh-faced initiate to a fully-fledged, competent professional. Having gained the skills required to succeed in their field, they now need to focus on continual development, gaining mastery in all relevant domains.

And, truth be told, once they’ve truly ingrained the mindset of prioritizing the goal of the tool, they’re in a good place. This is the most important lesson that they’ll learn in their journey – everything else either build up to it or complements it.

However, it’s one thing to understand that the goal matters more than the tool… and it’s another to know how to make achieving these goals as easy as possible.

To clarify, we’re not talking about “setting goals” here. This isn’t about applying the SMART model to your sales targets. It’s more about understanding when to use these tools, as well as who to use them on.

As the Chinese Warmaster Sun Tzu once said, victory or defeat is a product of preparation. A salesperson that expects to convert a prospect without first dedicating themselves to fully understand the client, their business, the tools at their disposal, and the impact of the broader environment will inevitably fail.

A good salesperson will understand the best way to make a particular conversion.

A great salesperson knows which clients are the most promising, and know the best time to target these people.

This is seen on both a macro and micro-level.

On a micro-level:

- They should know what times of day their prospects are easiest to reach and most receptive to being pitched. For instance, certain clients may be more accessible early in the morning, before they’re swamped by meetings and their regular work for the day. This particular information will be partially acquired in level 2, by experimenting with the tools they use. In our cold-calling example, they may note that they consistently get through more often in the morning than any other time of day. Conversely, other tools may fare better in the evening – direct face-to-face meetings, for example.

The critical distinction: if all tools produce similar results, then you can consider the result to be independent of the tool… and therefore it’s a strategic issue. However, if you haven’t devoted enough time to truly optimizing a tool in level 2, you won’t know the difference between a true result, and failure arising from poor performance. - They may also know that this client hates being cold called, tending to do business with people they know and trust. This relates to the effectiveness of a particular tool for converting a certain prospect. To gain this knowledge, your employee needs to put in their time, research the client, and try to gain an understanding before the first approach.

On a macro-level:

- A good salesperson understands the wider forces that influence a prospect’s buying decision. Stuff like market trends, time of year (e.g. lots of retailers will buy more stock before the busy Christmas season), and changing government regulations all play a part. By taking these factors into consideration, great salespeople remain two steps ahead of potential problems, safeguarding their chances of conversion.

- Additionally, they must also be aware of standard practices in the industry at large (e.g. if decision-makers in the sector at large are open to cold calls, then it’s a viable method).

Truly great salespeople develop this strategic approach to the application of their tools, developing the understanding required to succeed in their profession.

When it comes to our construction trainee, this level is very much just a continuing progression towards final mastery. In Level 3, they started to prioritize outcomes over tools, trusting in their experience to help guide them to the right decision. Here, they further develop this experience, learning those deep lessons that are paid for with time, energy and dedication.

They may learn to discard certain tasks which are no longer deemed necessary. They may also learn which processes are best done concurrently (e.g. pouring footers while building wall frame sections), and which are best kept separate (e.g. pouring footers while digging close by).

This knowledge is often imparted from observing more experienced employees, but it will take the trainee some time to fully understand why things are done this way. It’s one thing to mimic – it’s another to know the true meaning of what you’re mimicking.

It’s at this point that our trainees can finally say that they’re done. They’ve ascended as high as their positions will allow, and – truth be told – there’s no reason for them to go any further.

However, there’s still one more level for us to review… and it’s one that will be of particular interest to you. As a business owner, it’s your primary focus. Understanding how it relates to the topic of training and development will be a massive boost to your chances of business success.

Level 4. Leadership

Leaders: the people at the top of the organization that tells everyone else what to do.

A crude definition, but a fairly accurate one.

The leadership level is the highest point on our pyramid. From atop this lonely perch, the people trusted with guiding the company need to answer the most fundamental question of all….

Why?

Without the why, everything else falls apart: employees robotically move through the motions, customers buy when it’s convenient, people look for something more compelling to dedicate themselves to.

Your “why” is derived from your purpose and values. Your values are the things you hold to be most important as a business – you aim to live and die by them.

Your purpose is facilitated by sticking to these values. They should make it easier for you to walk the path you’ve chosen, not harder.

Your “why” is a product of the two. It’s the lifeblood of the business, giving birth to your strategies, tactics, and operations.

Goals

Goals set at this level will be high-level e.g. “grow revenue 10% this year”. These goals will be something that the actions of employees must be geared towards but aren’t useful guides by themselves. In order for these goals to be achieved, you need to distill them down through the lower levels of the pyramid, creating practices, processes, and structures which serve them.

It’s also important to remember that we must keep “mission over metrics” in mind. When chasing revenue increases, the actions we take must be dictated by what we deem to be acceptable as a business. Defrauding your customers to a bigger bank account is one way of growing revenues, but it probably doesn’t fit in with your vision of the business. Without truly understanding your “why”, everything is a possibility. Do everything you can to eliminate these unwise courses of action from consideration – know what you stand for.

As well as helping you to avoid the allure of criminal activity, your “why” is also the thinking behind your training systems, your routine procedures, your way of doing things. If you have a strong, clear “why”, these things naturally fall into place.

By understanding these four levels (Operational, Tactical, Strategic, Leadership), we can clearly see why organizational hierarchies exist.

Leaders determine the purpose and values…

Executives communicate the “why”…

Upper management deals with strategy (who and when)…

Middle management deals with tactics (how)…

Supervisors deal with operations (what employees do)…

And employees just focus on doing.

It doesn’t matter how big or how small your company is. Even if you only have 10 employees, these layers still exist. You may not explicitly have someone occupying the “executive” role, but that doesn’t mean you can neglect the responsibilities attached to it. In brand-new businesses, the owner rarely has the luxury of simply being a visionary. They will often play the role of manager, supervisor, strategic analyst, customer, employee, consultant… the list is endless and exhausting. Not all these roles will get the same attention, but they all matter.

Each position in the hierarchy has a purpose. These purposes have emerged from necessity – they’re a critical part of doing business well. Think of them as spokes in a wheel. If one is missing or in disrepair, the wheel will collapse as soon as it’s subjected to the pressure of the road.

Your leadership needs to think differently about training and development. They’re not necessarily participating in it (although we must always focus on improving ourselves), but they have a huge role to play in its design.

Conclusion

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this article. At the start, we were focused on how the learning needs of the individual will change as they develop professionally. To better understand this, we decided to focus on one general model for employee training and development, demonstrating how it maps perfectly onto our organizational pyramid.

This model is as follows…

Level 1 – Operational (Skill Acquisition)

Novices only need to focus on being able to do the thing reliably, without paying too much attention to the outcome. They aim to ingrain the habit of simply completing the action (within certain parameters) on a consistent basis. This sets them up nicely for success in the future.

Level 2 – Tactical (Performance Optimization)

When they’re slightly more advanced, it’s time to look at how well they’re performing. At this point, your focus should shift to optimizing performance with a particular tool – getting as good as possible at the task in question.

Level 3 – Strategic (Strategic Development)

Once their performance is optimized, it’s now time to shift focus away from the tools, and instead learn to prioritize the outcome above all else. Having mastered their use of a hammer, they now branch out and complement this tool with an array of others, all geared towards achieving your ultimate business objective.

Level 3.5 – Even More Strategic (Deep Understanding)

On a higher level, the employee learns how to be even more strategic in their approach. They consider not only which tool to use, but also who to target, and when to do so, and how to optimize their every action for top performance. These skills are difficult to communicate and difficult to acquire, but they are enormously beneficial to possess.

It’s at this point that the training and development needs of the ordinary employee are met. However, we still need to discuss the apex of the pyramid – leadership.

Leaders have to think differently. They can’t be too concerned with who, what, when, or where… their only focus is “why”. Everything else in the business trickles down from this “why”, so it’s important to ensure that it’s well-chosen.

This pyramid model of training and development helps us to understand that it’s a continuous process. It’s never truly over and done with – there will always be new employees to initiate, new skills to learn, and new situations to adapt to. The pyramid we stand upon returns to the dust, and we’re left with no choice but to set out again, confident that we can reach the peak once more.

Well-trained employees are your best defense against business failure. If you hope to succeed, you need to pay attention to this whole topic of training and development.

Like everything else in life, you have a choice. You can take charge of your organization’s training processes… or you can choose not to. Just know that if you don’t make the effort, the only result you can expect is to create employees who don’t understand your vision, don’t understand your business, and can’t adapt to change effectively.

It’s obvious, isn’t it?

Make your choice. Train up the pyramid, and win the battles before they’re fought.